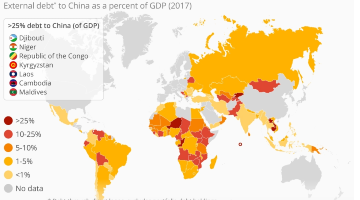

The enormous increase in lending by China to lower and upper middle – income countries, principally under the banner of its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), has been met by the West with varying degrees of concern not least because so little was known about the terms of that lending.

Now the How China Lends study, published this week and led by the AidData research lab at William and Mary college in Williamsburg, Virginia has published the most comprehensive review yet of such terms. Out of the 2,000 or so loans signed mostly between state – owned China Development Bank or China EXIM and sovereign borrowers (or borrowers guaranteed by the state) since 2000, the researchers managed to unearth details of 100 loans to 24 countries worth a total of $36.6 billion. They then benchmarked the Chinese loans to a sample of 142 loans from 28 commercial, bilateral and (mostly) multilateral lenders (let’s call them the West). At 85 pages, the report passes the thump test.

The results will disappoint those who have argued that BRI is little more than debt trap diplomacy for the study found that China’s terms were generally not so unreasonable, even considering that sometimes there was no alternative source of funding from the West. At the same time, however, there were several features to worry about.

The study has three main findings.

- Confidentiality clauses are common in the West but their contents tend to leak out to the wider world a lot more easily than have those from the BRI, hence the significance of this study. Such clauses are all rather well but barring borrowers from even revealing the existence of a loan takes matters too far. Other lenders, not least the likes of the IMF, need to understand a host government’s aggregate borrowing and its required repayment schedule – no secret debt please.

- Much of China’s sovereign lending / BRI has been to borrowers with low or no credit ratings. Outcomes in Pakistan, Kenya and elsewhere have demonstrated how risky this was and have justified the West’s caution in lending there. (Has China been looking for political leverage over these countries? Of course it has, as to some extent do all sovereign lenders.) Thus, default provisions are more likely to be invoked than is perhaps usual. Even in the best of times, when borrowers default, there is an almighty scramble by each creditor to get repaid ahead of the others – it might be called the EMFH strategy as in Every Man For Himself. (Witness last week Goldman and Morgan Stanley exiting their outsized exposures to Archegos ahead of, and thus with much less pain than, Credit Suisse and Nomura.) The Paris Club of sovereign lenders seeks to impose order on this chaos but China is not a member and many of the loans in this study specifically excluded cooperation with the Paris Club looking to effectively grant China a preferred creditor status. Since these loans were signed, however, China has undertaken to cooperate with the rest of the G20 by joining the Debt Service Suspension Initiative (DSSI) for poor indebted countries and the Common Framework for Debt Treatments beyond DSSI, announced in November 2020. How this plays out remains to be seen.

- The study found clauses on cross – default (immediate repayment required if an unrelated loan defaults) and cross – suspension (pause drawdowns of the loan) which were defined much more broadly than is usual. Examples included any action adverse to China’s investment interests in that country (!) or termination of diplomatic relations (by which side?) On the face of it, this broad wording looks alarming especially when its interpretation lies in the hands of a Chinese court (see below). On the other hand, what would the practical implications be? As J.M.Keynes, Alan Bond and many other luminaries have argued, if you owe the bank $1 million it’s your problem but, if you owe the bank $100 million, then it’s the bank’s problem. Besides, debtor countries may have only limited assets outside their country capable of being seized by a creditor.

More specifically,

- The two samples both show a range of interest rates, grace periods and loan tenors on the basis of which the China loans are not so unreasonable.

- The study addresses sovereign lending rather than lending with recourse limited to projects – but, in practice, there may be little distinction and the Chinese loans borrow some concepts from project financing. Thus, off – shore escrow accounts and change of (host government) policy clauses are common in project finance, less so in the West’s sovereign lending, but perhaps not so unreasonable here.

- Rarely do Chinese lenders take security over physical assets (a process which can be fraught with complexity and uncertainty in local law and whose effectiveness is often unproven).

- Instead, the debtor sometimes posts other collateral, for example, agreeing to sell a certain volume of oil over the life of the loan (presumably at prices prevailing from time to time) to, say, PetroChina with the proceeds first deposited in the accompanying loan’s escrow account.

- China EXIM requires that governing law be China’s with arbitration in China at CIETAC (not great from the debtor’s point of view); CDB is more commercial with English or New York law. (HKIAC has been promoting HK as a neutral venue).

The study necessarily does not address the wider picture.

- The West has stayed away from BRI for a variety of reasons i) poor project preparation ii) poor borrower credit worthiness / poor project viability iii) Chinese lenders usually stipulate that Chinese parties act as contractor or operator of projects (not unusual for tied aid) which they can do more cheaply than Western counterparts anyway iv) poor standards of Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) matters – i.e. all the difficult stuff about land acquisition, caring for the local population, skills transfer, the water supply, air quality and much more – which have become more significant post Covid v) political jealousies.

- BRI lending has thus needed to be bilateral – indeed, the study found that the average CDB loan was a thumping $1.5 billion.

- Responsibility for signing these loans lies just as much with the debtor governments. Yes, they need to understand what they are signing; yes, they need to do so for the greater benefit of the country as a whole; yes, they should pitch one eager lender against another so as to create some competition; yes, they need to then spend the proceeds of the loan wisely which includes Properly Preparing the Project, whether the project is financed via sovereign loans or via the more disciplined project loans. These are difficult, high value, long dated, politically sensitive issues confronting often inexperienced and poorly paid personnel who should not be afraid to learn from other countries’ experience. Logie Group has advised on all of the above.

As I have written in the past, the impact of unprecedented Chinese lending for mainly infrastructure will be determined not least by the rest of the World’s response to it. With Covid having normalised previously unimaginable levels of government spending, the US in particular is now promising huge sums and not just domestically. There is competition; let’s hope that there is collaboration; but most importantly, let’s also hope that the money is spent wisely.

Map source: Statista