Labour will win the UK general election on 4 July (hey, I’m going out on a limb here) but, in doing so, has allowed the undeserving Conservatives to salt the earth that Labour will inherit. There is to be no new borrowing, no cuts to services and no increases in the major taxes. So where on Earth (salted or not) will the money come from to spend anything on anything, infrastructure included?

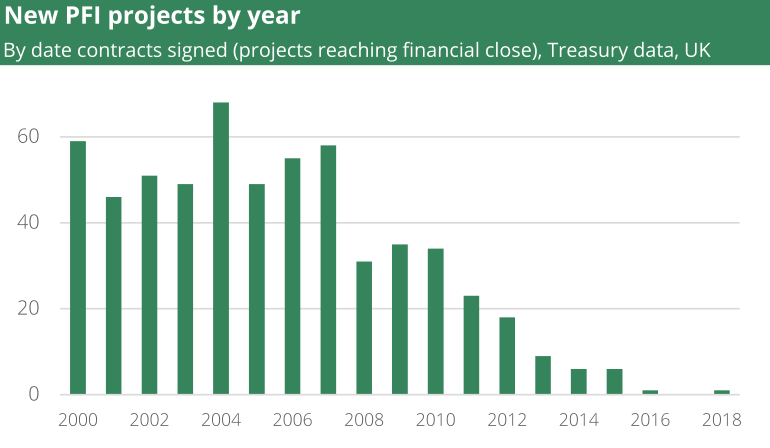

A lot more will be needed than further tinkering such as folding the Infrastructure & Projects Authority and the National Infrastructure Commission into a National Infrastructure and Service Transformation Authority. Much more impactful and largely overlooked by the commentariat would be to revive an old idea by returning to the much – derided Public Private Partnerships. All that is needed is to add a (significant) bell and whistle or two.

Ms. Reeves’ plans rely heavily on a sudden increase in growth. She has not said much on where this will come from but the two obvious candidates are i) taking a scythe to a sclerotic planning system, the poster child for which is the Lower Thames Crossing, a 23 km road and twin tunnels under the river east of Dartford, whose planning application in January, 15 years in the making, ran to a scarcely believable 359,000 pages and itself cost £300 million; and ii) more efficient trading with the EU – yes, let’s reopen Brexit! That’s for another day.

The private and public sectors combine in a wide variety of ways, of course, when it comes to the former providing infrastructure services previously delivered by the latter. At one end of the spectrum, privatisation has offloaded entire industries into private hands leaving the govt with little to do beyond regulatory and rescue roles. Telecoms and power generation were transformed; water has suffered from feeble regulation; rail was never going to be viable on a stand alone basis and degenerated into a mess with no one seemingly responsible for anything.

In contrast, PPPs usually refer to individual assets which are not only built but also operated by the private sector which sometimes – and sometimes not – takes the associated revenue risk. It is not usually expressed this way but they are a (welcome) sleight of hand where the bulk of the debt and equity funding comes from financial institutions, developers and such which have enormous amounts of “dry powder” itching (sorry) to be invested in long – dated, inflation – linked and (hopefully) relatively safe investments – whilst the govt takes on the risks that the private sector won’t so as to make the project actually happen. When govt book keeping is largely cash – based, it can contribute contingent obligations and assets other than cash without breaching their cash – based election manifesto promises. Voila! Ms. Reeves’ conundrum is resolved.

Thus, govts the World over can justifiably expect to leverage their contribution and crowd in private sector money (Ms. Reeves’ £7.3 billion National Wealth Fund hopes for three pounds of private money for every one of its own)

… so long as the private sector is presented with risks that it can either manage (e.g. build a road but not necessarily take traffic risk on it) or at least is prepared to take (e.g. the market price of output from a mine); and is rewarded accordingly.

The tweak necessary to make project risk profiles acceptable to the private sector is for the govt to be much more flexible / imaginative in the support which it provides. Blanket guarantees will not be on offer but nor are they needed. Lost in the mists of time (1991), the London project finance market came of age with the Teesside Power IPP where pre – Andy Fastow Enron offered a dozen tranches of contingent subordinated debt, each targeted at a particular risk – and, as it turned out, none of which was needed. The Korea govt has offered revenue collars such that it topped up revenues if they fell too far, in return for which it shared in any upside – which it withdrew once the market had matured. Australian and Canadian investors, flush with mandatory pension contributions, have recognised attractive opportunities when they saw them, not just at home but also further afield, not least in the UK, of course. Even countries like Indonesia have side stepped dishing out MOF guarantees by housing contingent obligations in quasi – govt bodies such as the Indonesia Infrastructure Guarantee Fund, staffed by private sector risk assessors rather than by civil servants and set up when Andrew was advising the MOF. When the compulsory purchase of land is so fraught with uncertainty, govt can contribute its own land whilst still adhering to those pesky manifesto pledges.

Of course, this support needs to be allocated and rationed – but it also needs to be recycled once a project demonstrates that it is no longer needed, typically after a year or two of successful operations as, for example, demonstrated via reassuring debt service cover ratios. However, recycling of support has rarely been explored in the UK or, indeed, anywhere else. Likewise, sharing risk as opposed to offloading it entirely.

And when PPP contracts are long term, the service which they deliver will inevitably need to change. Will that road built today be in 25 years’ time full with EVs navigating themselves within a few feet of each other – or empty as everyone stays at home in their pyjamas using virtual reality for everything and relying on drones to deliver the shopping? Again, flexibility and imagination (not to mention goodwill) will be necessary when writing contracts of this duration.

Whether this approach can be used to revive Labour’s pledge to mobilise £28 billion of spending on renewables remains to be seen. Renewables bring their own challenges, both micro and macro. Watch this space.

Four months later, the Times catches on …

Broke Britain’s roads and rail need fixing — so PFIs to the rescue