Lost in the excitement of the Chief Executive election in Hong Kong last week was the news that the Environmental Protection Dept had approved an amendment to a proposal by HK Electric to build a 150 MW wind farm off the south west coast of Lamma island. Tendering for the wind farm will start in 2024 and commissioning in 2027.

Immediately,

- The project is small in that it will produce just 4% of HKE’s electrical output (and intermittently so) and 2 % of HK’s (it’s a rounding error for China).

- It is expensive. HK’s other power utility, CLP, is also proposing its own wind farm of 255 MW at South East Ninepin in eastern waters. Taken together, the government estimated in its Climate Action Plan 2050, published in October last year, that 300 MW would cost HK$10 billion or US$4.2 million / MW (numbers are moving around a bit).

- And HKE currently doesn’t need it in that the capacity of its sole coal – and gas – fired power plant is 3.6 GW whilst peak demand is 2.3 GW (2020 figures). A 56% reserve margin is huge.

After all, HK and thus HKE can afford it.

Is this just filling up more of HK’s waters not already consumed by the gargantuan US$64 billion (pick a number) Lantau Tomorrow Vision white elephant, 10 km to the north? (LTV has recently been rebranded Central Waters which makes it sound like a dormitory suburb in California but by rights it will be displaced by the US$13 billion + (pick another number) Northern Metropolis anyway.)

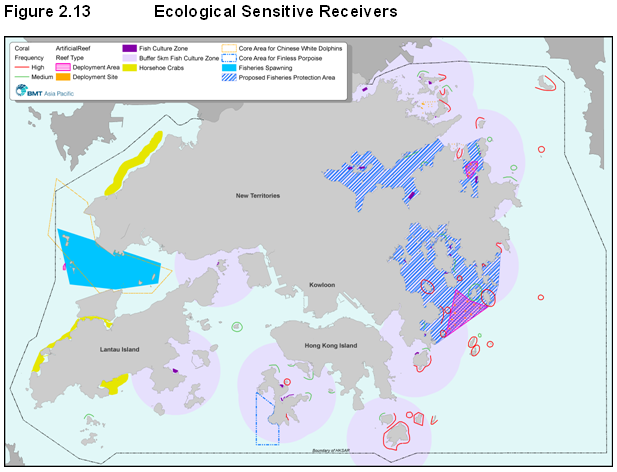

Not to mention upsetting those white dolphins displaced by the third runway set to open later this year if there are any passengers; or the green turtles last seen nesting on Lamma’s Sham Wan beach in 2012?

- Decarbonising the World is going to be expensive and it has not been agreed who will pay. Rich places like HK should lead the way. The government’s plan calls for 7.5 – 10% of the territory’s power to come from renewables (wind, solar, Waste to Energy) by 2035 and 15% by 2050. (25% already comes as nuclear, imported by CLP from Daya Bay.)

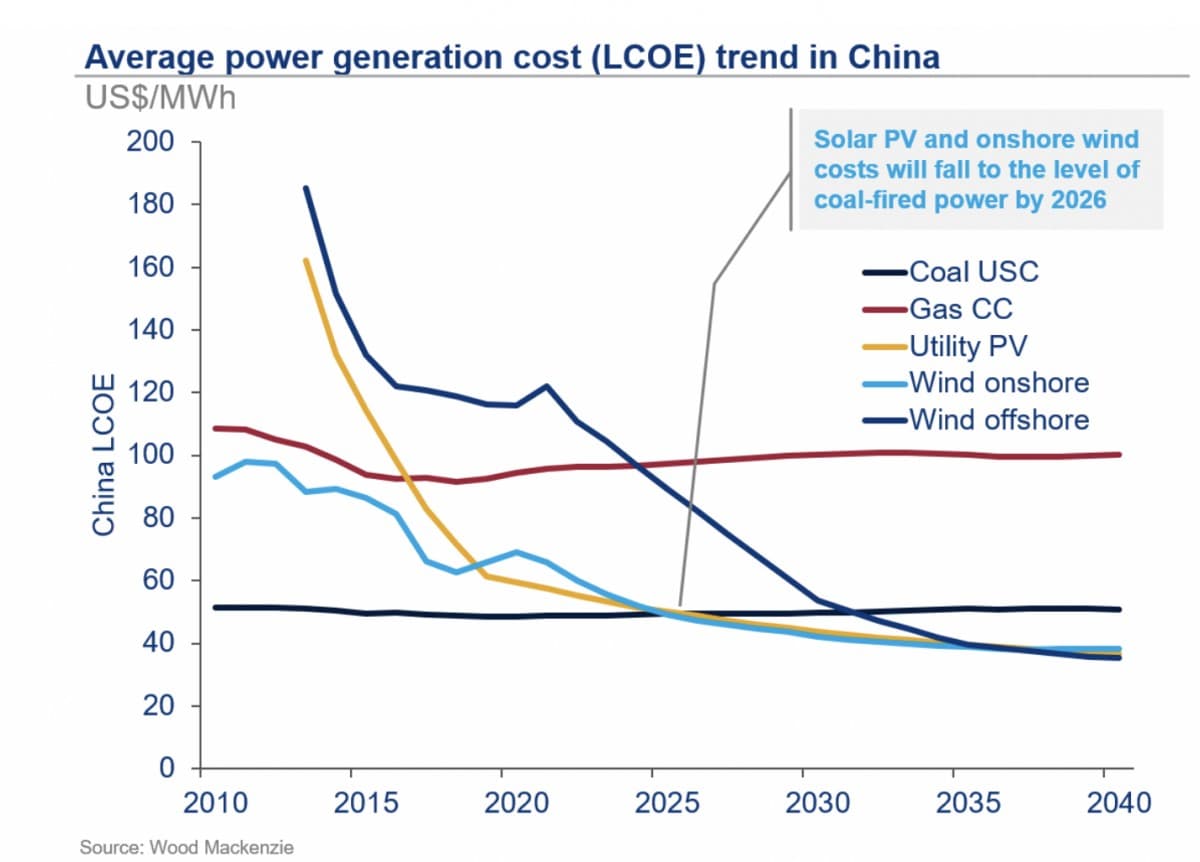

- Yes, offshore wind is expensive – compare its Levelised Cost of Electricity per MWh (i.e. spreading the capex over the useful life of the asset) to that for other fuels. But it has come down dramatically in recent years – the chart shows both points. HKE built an 800kW turbine on Lamma in 2006 and first obtained an environmental permit for the full – scale wind farm in 2010. Waiting twelve years has, by luck or judgement, meant that this power will be much cheaper than if they had pushed ahead – a dilemma familiar to all developers of wind and solar.

- But the financing decision is more a political one than a commercial one. The cost will effectively be borne by consumers as the capex (of perhaps US$450 million) will be included in the company’s next five – year development plan for 2024 – 8; this will need to be approved by the government as HKE’s tariffs are regulated so as to yield an annual Permitted Return of 8% on its average net fixed assets (subject to various performance incentives and penalties) under its Scheme of Control Agreement with the government. When electricity generation accounts for 66% of carbon emissions in HK (2019 figures), HKE and CLP can be confident that almost any sensible renewable project will be approved.

- It enables HKE to develop expertise which can then be exported as CLP has been doing in India and Australia, as have the MTRC (rail) and the Airport Authority (er … airports).

- And once up and running, the windfarm is a discrete asset which can perhaps be sold to an asset manager (if envisaged under the SCA). Global Infrastructure Partners have this month bought wpd’s offshore windfarm portfolio of five projects underway (including Yunlin in Taiwan) plus 30GW under development (price not disclosed).

Both HKE’s and CLP’s windfarms should therefore be worthwhile and will be funded on balance sheet.