And now for something completely different …

Relationship banking, name lending, call it what you will, “lifts the corporate veil” which draws a legal distinction between a company and its owners in that banks place some reliance on whoever owns or controls the borrower. More generous terms are perhaps extended, margins reduced or the loan made when otherwise it would not have been. Banks may grit their teeth but they usually lend the money; and the borrower usually repays it even if the owner needs to help out and thus preserve his and his company’s reputations for next time. Whole industries are built on this.

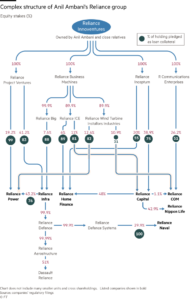

Ten years ago, the IPO for Anil Ambani’s Reliance (capital R) Power raised $3 billion in one minute. The issue was oversubscribed 10.5 times valuing RP at more than NTPC, still the largest power producer in India operating 28 GW of power plants with a further 50 GW planned and still owned 54% by the Government of India. All this, despite RP not actually owning any assets at the time. Few individuals could have inspired such trust.

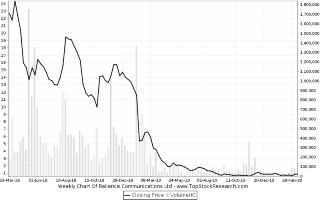

Reliance Communications inspired similar, if less visible, zeal to build out a mobile phone network.

But RP failed to develop any portfolio of Independent Power Projects and RC fell victim along with others to the price war started by Mr. Ambani’s elder brother Mukesh’s Reliance Jio, filing for bankruptcy in 2019. Last week, Mr. Ambani jnr alleged that his $40 billion fortune had shrunk to zero.

He made his claim in the UK’s High Court where he is being sued for repayment of a $700 million loan to RC in 2012 by ICBC, China Devt Bank and ChExim, a precursor to the Belt & Road Initiative. The Chinese banks assert that he personally guaranteed the loan. He retorts that the document in question was merely a comfort letter and, as such, not legally enforceable.

It depends, of course, on how the document is worded. It is unlikely that the word “guarantee” is used or, if it is, what is being guaranteed may not include the loan principal. Oh, to be a fly on the wall!

But is there a cultural disconnect? Way back in 1986, when Project Finance was cutting its teeth, Japanese banks lent more money to Eurotunnel than did British and French banks combined because Margaret Thatcher had gone to Tokyo to sell the merits of the Channel tunnel despite just having passed a law forbidding the British government from supporting it. The Japanese thought that Eurotunnel was quasi sovereign risk only to find that it wasn’t. Back with RC, the Chinese were encouraged by a recent revamp of India’s previously sclerotic bankruptcy laws aimed in particular at so – called promoters such as Mr. Ambani who, despite being supposedly bankrupt, continued to live rather well.

Investors like to think that infrastructure can be considered a separate asset class due to its stable, long term, inflation – linked returns – but this may not be so. Large capex is required which brings risk of cost and time overruns; political uncertainty revolves around approvals regimes; and the revenue line is hugely volatile. In the power sector, the revenue risk can be passed on to a hopefully creditworthy customer via a traditional Power Purchase Agreement. In the water sector, a concession typically allows for a certain rate of return on assets, making them very attractive. In telecoms, as the younger Ambani found, there is no such protection and you are relying on rampant growth to outweigh market and technology risk then plenty of equity.

RC or the Chinese should have sought advice from Logie Group (fees are very reasonable…). The old saw – and no less true for that – is that lenders should instead take their comfort from carefully structuring the project / business such that risks are allocated to those parties willing and best able to accept or manage them.

Over the years, Moody’s have consistently found that Project Finance debt performs similarly to corporate debt rated low investment grade (annual updates are generally issued in March – this year’s will be interesting). Most banks would settle for that as opposed to the loose structures of name lending into opaque conglomerates where the defining maxim appears to be Caveat Commodator.

(As dictated from behind the sofa as my pension disappears …)